“Science and Mysticism: New Novel ‘Child of Light,” Interview, Jesi Bender and Wesley R. Bishop.

In the summer of 2025, novelist and librarian Jesi Bender released her fourth book, Child of Light. Set in 1896 upstate New York, the novel follows Ambrétte Memenon as she reunites with her family amid a world transformed by both spiritualism and the rise of electrification. Blending mysticism and science, Bender captures the way history has often entwined belief and fact. In this interview, she speaks with managing editor Wesley R. Bishop about her background, her craft, and the inspirations behind her latest work. The following has been edited for clarity and length.

Wesley R. Bishop: Can you start by telling us a bit about yourself?

Jesi Bender: I grew up in upstate New York, on a really rural farm where we raised Black Angus beef. I went to Cornell as an undergraduate, but from the start I wanted to be a writer. As a kid, my grandmother always took us to the library, and I remember in sixth grade picking up Cat’s Cradle by Kurt Vonnegut. I became obsessed with him—and still am to this day. Later, in eighth grade, I read The Great Gatsby. It was the first time a teacher explained symbolism to us—those eyeglasses representing God—and I thought, ‘Oh my God, I love this.’ That’s when I knew I wanted to write. I began publishing in college, mostly poems here and there.

I moved to New York City to try to be an artist, but I was so poor—just scraping by. Still, a lot of creative, sustainable projects came out of that period. Eventually, I moved back up here, and since then I’ve been fortunate to publish some plays, a few chapbooks, and now this, my second novel. My work really centers on experimental writing—playing with form, challenging language, and questioning how we make meaning. I’m also always drawn to history, so most of my work ends up being historically rooted, which is very much the case with this book. And outside of writing, I’m a librarian.”

WRB: You work as an academic librarian correct?

JB: I’ve always been an academic librarian. I used to be in a more patron-facing role, which I kind of miss. I worked at a small liberal arts college, and as anyone who’s been at one knows, you end up with five jobs rolled into one. I handled web work, but I was also teaching in the arts, managing collections, and doing a lot of purchasing. If you ever visit Colgate University, they have a wonderful independent press section—that was something I spent a lot of time building. These days, though, my role is more on the IT side. I focus on maintaining the library website and working on the software development projects we take on.

WRB: You spoke a bit about your background and becoming a writer. Could you walk us through your previous works and how it led you to this newest novel Child of Light?

JB: The first thing I ever published were poems in a student magazine at Cornell—Footprints, as far as I recall—even though I don’t think it still exists. Those early pieces were deeply rooted in imagery of God. I’m not religious myself, nor is my immediate family, but I’ve always been fascinated by religion, and that interest shows up in this book too—not in Abrahamic faith, but in spiritualism, the idea of death, and people declaring confidently what happens after we die.

I began writing a novel in college, and that project followed me throughout my years living in the city. After many drafts, it was finally published in 2019 as The Book of the Last Word, by Whisk(e)y Tit Whisk(e)y Tit+1. The book traces a character compiling famous last words before people pass away.

More recently, I published a play with Sagging Meniscus press—and was lucky enough to see some productions of it.

I tend to write poems and short stories in quick bursts, but usually I’m also working slowly in the background on a much longer project that takes time to develop.

WRB: Would you say there is a theme of spirituality, or curiosity about religion, that runs through all of your work?

JB: I think a lot of my work comes from a kind of existential dread. Even if it’s not explicitly religious, I’m drawn to anything that touches on these larger, unknowable questions. For example, my play Kinderkrankenhaus is about autism, but at its core it’s about meaning-making—how difficult it is to understand one another, even with so-called normative expression. With language we only ever grasp a fraction of meaning and have to derive the rest. That play isn’t explicitly religious, but it is rooted in the same questions that guide much of my writing: how we construct ourselves, and what might exist outside of us. Those ideas are always at the heart of my work.

WRB: And so you said that you were inspired by Kurt Vonnegut? Our press started in Indianapolis so, as a former Indianapolis resident, shout out to Kurt! (Laughs) You also said F. Scott Fitzgerald. Who are some other writers that you read and you find yourself in conversation with?

JB: There are so many writers I love, but three living authors stand out for me. The first is Carole Maso—she actually blurbed Child of Light, which I still can’t believe. I didn’t know her, but I wrote to her and said how much I admired her work, and she graciously agreed to read it. She’s incredible. For anyone looking to start with her, I’d recommend Defiance—it’s just wonderful.

Another is Thalia Field, who I believe still teaches in Brown University’s creative writing program. She does fascinating, experimental work.

And then there’s Salvador Plascencia, who wrote The People of Paper. As far as I know, it’s the only book he’s published, but I think it’s brilliant and I really hope he continues to write.

Beyond that, I love poetry and read a lot of poets. Recently I discovered Peter Weiss—new to me, though of course he’s been around for a long time. He wrote Marat/Sade, and also an incredible play about the Auschwitz Trials.

In general, I’m drawn to work that’s playful, imaginative, and willing to break away from convention. Even if I don’t absolutely love a piece, if it disrupts traditional forms and does something different, I’m always engaged.

WRB: That brings us to your new novel. Can you tell us a bit about your process in writing it? Some writers develop an idea and then set it aside for a few books, while others dive into entirely new concepts with each project. Where does Child of Light fit in your process?

JB: Child of Light was inspired by the city of Utica, New York. Like many upstate towns, it’s financially depressed now, but it once had wealth. That creates a strange mix: grand, ornate Victorian buildings alongside poverty and clinics, all interspersed. There’s something sad about it, but also something beautiful. I was particularly inspired by one house on Genesee Street—we always drove by it, and I called it ‘my house,’ imagining the lives inside.

Being a librarian, I dove into research. I joined the local historical society, literally across the street from the house, and explored every book I could find on spiritualism and local history. I also visited the archives at Hamilton College, which has a great collection. Since the book’s parents are French, I researched Paris of the period as well.

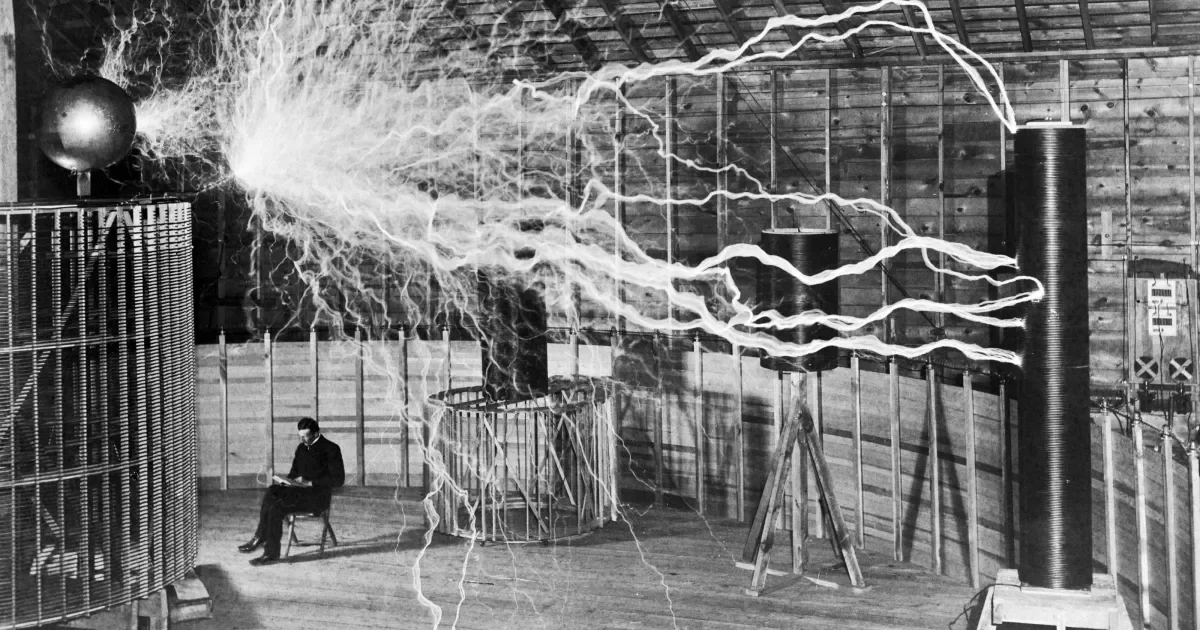

I’ve always loved the Victorian era—the late 1800s—because it defies the typical stereotypes. People were often eccentric, doing strange and unexpected things. It was a time of rapid technological and scientific advances, yet also of fascination with the occult, mysticism, and spiritualism. That tension felt very relevant today, so I wanted to explore it.

I researched early electrical engineering, French culture, spiritualism, and Utica history. From there, I take all my notes and organize them thematically…

WRB: That’s very librarian of you.

JB: (Laughs) Yes. Very. Once I have my outline and I begin from my notes where I want these different elements to show up. And then it's basically like making a sculpture. It gets more refined, more refined, and more refined.

WRB: So your interest in upstate New York inspired the setting, and the story developed from there. You also mentioned something fascinating about the Victorian era: the combination of major scientific and technological advances—not just in theory, but in everyday application—alongside a strong pull toward mysticism and the occult. In popular thinking, we often separate the two, as if you can have one or the other. You said this mirrors our own time. Could you explain more about why you see that connection?

JB: Child of Light was written mostly during Trump’s first four years, which makes it feel even more relevant now. In the book, the major scientific advancement is domestic lighting. I love thinking about how mind-blowing it must have been to see a light turn on in your home for the first time after years of candles.

I see parallels with today’s political climate, particularly the far-right push against academia and intellectualism. Growing up in one of the poorest counties in the New York State., I understand the frustration of seeing access to things you’ve never had—it can make you feel ignorant. But I’ve never understood the desire to attack research or intellectualism. We’re on the cusp of breakthroughs—vaccines for Alzheimer’s, cures for cancers—and yet those efforts are being defunded or attacked, often over cultural controversies like DEI initiatives or the inclusion of trans people in sports.

The book doesn’t directly tackle the weaponization of religion, but it does explore why the mystical and spiritual might have been so appealing, especially to women who were disenfranchised at the time. That tension between progress and mysticism is central to the story.

WRB: That makes sense. As you were working on this book, I’m curious: do you see anti-intellectualism—the attack on expertise and scientific knowledge—as inherently a right-wing impulse? And how does mysticism fit in—does it tend to align with reactionary politics, or is the relationship more complex?

JB: Oh, I definitely think it’s more complex than that. Anytime there are haves and have-nots, the haves often feel they deserve their position, while the have-nots recognize the rich were just lucky. The ‘have-nots’ can be any group—it doesn’t have to be right-wing, though in our current era, they often are. Throughout history, though, it’s been all over the place.

One area I’ve long been interested in is the French Revolution, which you can see hints of in this book, especially in how the father figure’s privilege and family background allow him to maintain power. But I don’t think one automatically leads to the other. People gravitate toward religion or spirituality when they feel isolated or disenfranchised. In Child of Light, women are particularly drawn to spiritualism—they endured the emotional repercussions of the Civil War and were navigating the beginnings of first-wave feminism, seeking power where they could. For the mother character, spiritualism provides a space where she can distance herself from men and claim some agency—a space where she can be on the ‘have’ side rather than the ‘have-not.

WRB: That’s interesting. I’ve noticed a similar trend in our own time—starting before COVID, during the first Trump administration, and accelerating through the pandemic—an increased interest in practices like tarot or stoicism. Stoicism, of course, has scientific backing in cognitive behavioral therapy, but it is ancient. And tarot and other mystical or alternative spiritual practices have become very popular. There’s a certain beauty in them. What fascinates me is that these ancient ways of knowing exist alongside modern scientific advances, including AI. So, for example, you can ask an AI bot to read tarot cards for you, or come up with a prayer. I think that tension— between scientific progress and mysticism— is something that really comes through in your book.

JB: Yeah, I agree. It’s really interesting. I think sometimes people are reaching—they want to feel something. As a writer, I’m not sure how you feel about AI, but for me, anything human-made, even if deeply flawed, is infinitely more beautiful than anything AI can produce.

WRB: We could easily talk all day about AI, and as a librarian, I see how complicated it is. Essentially, AI are information-retrieval systems pulling from huge amounts of data, often without clear controls. I’m curious to see where it goes. If you just ask it to ‘make a picture of a flower,’ you’ll get a pretty generic image, which might be fine for a lot of people. But who knows what advances will come, and what purposes AI will serve? These systems aren’t just about ingenuity or scientific exploration—they have commercial and military interests. That’s an aspect of scientific development we often overlook: it’s not just about creating something helpful, but also about who controls it and what they want from it.

JB: Yeah, 100%. You can see that tension destroy the father character in the novel. He’s an artist at heart and wants to create, but he’s undone by the business side of things.

Another thought that comes to mind about AI: one thing I really dislike is its corporatization and the way it replaces human roles. When I was teaching, I’d often say, these computers don’t care about you—they don’t care if your bibliography is correct. Yet we assign human responsibility and emotion to these systems.

The Victorians did something similar with electricity. Some saw God in it; they attributed spiritual significance to this new force. There’s even a famous poster depicting a spider-like figure made from wires, threatening and consuming someone. We try to make these forces ‘living’ so we can understand them, but that’s an error we repeat with AI—assigning agency and moral judgment to something that isn’t human, and then making real-world decisions based on it, like hiring or firing.

WRB: I agree—it’s fascinating how we infuse technology with human emotions and agency. In a way, it makes sense: we invented it, so we see ourselves in it. With electricity, it was ‘alive’—moving, switching on and off. AI is different, of course; it simulates consciousness, responding to our questions. At this point, many systems could easily pass a Turing test.

On that note, let’s dive a bit more into the book. For the readers, can you give us a summary of Child of Light?

JB: Sure! So, Child of Light follows a thirteen-year-old girl whose family is gathering in a new house in upstate New York. Her family has long been privileged but often apart—she was raised by a nanny, her sibling and mother pursued their own interests, and her father moved frequently for work. As they come together, they’re trying to understand what it means to be a family.

The mother embodies spiritualism and seeks to establish herself in the community through it. The father represents science—he chose Utica because of Trenton Falls, an early electrical site. The protagonist, meanwhile, is learning how to navigate her family and her own place within it, trying to reconcile the gaps between them.

WRB: And what projects are you working on next?

JB: I’m currently wrapping up a novel about Grace Brown, who people might know from An American Tragedy by Theodore Dreiser. It’s another upstate New York story—funny enough, I live on a dirt road in the woods, and she lived just a hill over, so it’s a kind of local, small-world connection.

I also have a play coming out next year called Crux. On the surface, it’s about Bobby Sands and his hunger strike, but more broadly, it explores the role of violence and non-violence in revolution, with different revolutionaries visiting him throughout the play. I’m really excited for its release next year.

WRB: Congratulations! Any final words for readers?

JB: I really appreciate your time. Readers can check out my website at jesibender.com—I’ll be doing some public readings throughout the summer. One last thing: when I was talking about authors I admire, I also want to mention Vi Khi Nao—she’s amazing, and I wanted to make sure to include her.

WRB: What should people read of hers?

JB: Vi Khi Nao has published a lot of fascinating work. She has a book called Funeral, though it was part of a dual release. She also published Suicide with 11:11 Press, which is incredible, and The Italy Letters, her most recent book from Melville House. She’s prolific, and there’s a lot of great work to explore.

WRB: Well, after folks are done with Child of Light they will have to read those as well! Thanks for sitting down with us at North Meridian.

JB: Thank you!