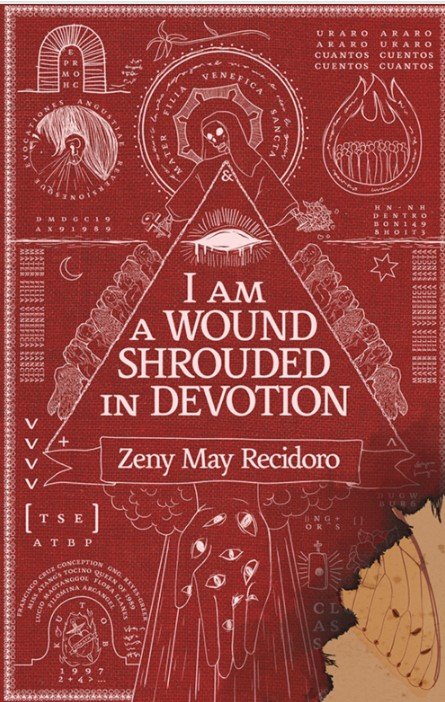

Book Review: “I Am a Wound Shrouded in Devotion.”

Zeny May Recidoro. 2022. I Am a Wound Shrouded in Devotion. Bay City, Mich.: Alien Buddha Press,

117pp. ISBN 979-8846451971.

Reviewed by Christopher Heisserer

Zeny May Recidoro’s debut foray into book writing resonates through me like a church bell. Some might say this is a collection of short stories, flash fiction, and poetry that, when woven together, creates a flourishing narrative about the history, inextricable humanity, and community of the island of Balaybay. I say this is a collection of prayers whispered into earthen pits. Recidoro’s accolades and awards are numerous, with the Asian Cultural Council fellowship, a BA and MFA in Art Writing and Criticism, and a list of publications from the University of Hong Kong to the Journal of Contemporary Philippine Literature.

A summary: the twin towns of Antik and Santa Lucia have a history of suffering. Even as the names suggest, it was the center of a clash of cultures. And nestled between those two towns, an unnamed and “forgotten” church that has fallen into disrepair and disuse. Yet it becomes clear that those who live in the towns have a place of adoration and respect for the church, and even remember the sound of the bell that has long since gone missing. As her own church, Floria Llanes seems forgotten and ignored, yet her existence sends ripples across the community and her family: who she was, how she connected to the community, how her faith allowed her to transcend the struggles of Filipino life. Her life, and her death, means something. Like the memory of a bell, Floria’s echo seems almost subconscious to those who knew her.

There is a timelessness to this book. I did not grow up in the cultures that grew this book, and yet I felt the power of them in my very bones. Awash in Philippine myth and Spanish faith, the two towns of Antik and Santa Lucia could not be more direct in metaphor. Recidoro’s storytelling is concise and lived-in, with a robustness that makes me feel I’ve known this place my entire life, that I am privy to its rituals, sermons, and people. I found comfort in whispering prayers into holes beside the church.

This is a book about people. The multivoiced nature of this commentary—that, I must add, endeavors and succeeds in constructing a shared insight surrounding the disappearance of Llanes—takes a little getting used to. I am a Wound is not chronological and not singly narrated. It is full of differing voices, insights, and perspectives that fill the narrative with a robustness at home in a Saunders novel. Unfortunately, with the prevalence of so many opinions and conversations, sometimes with whole sections titled “Fifteen Beginnings or, Stories without an Ending” that promote an environment of bustling, lively existence but adding little to the primary story, I found I lost the thread of inquiry several times along the way. Yet, it only invited a second read to collect the little bits of information.

Recidoro’s skill with the word is rich and vibrant, haunting, and fleet-footed in turns.

This book chases memory. It leaps between times, across decades, the present and past, to tell the story of Spanish colonization, the loss of innocence, and the safeguarding of artifact and self. After several read-throughs, I returned to the first passage titled “echoes from a tender ritual,” where the daughter of Floria, Esther, had her single interaction with the nameless church. Her longing seems to be my longing. Her memory, of course, is her own.

The postmodern, experimental approach often vitalizes the text in ways that straightforward writing otherwise would not. For example, “Subterranean Woman” has two lines but four footnotes that not only take up the remainder of the page with personal reflection, but also bleeds into the next. The beautiful lines “Grounded within herself, she knew her interior life/was the exoskeleton with which she met the world” scaffolds the footnotes almost like a stained-glass window in a church, with the lines themselves becoming symbol for a greater story beneath. It becomes more than a study in footnotes, but a study in life choices determining word choice. On the other hand, the experimental approach sometimes falls a little short in the reading, with added periods, hanging commas, and word choices that might be a miss in formatting, might be an artistic choice. There were—notably few—moments where I had to leave the end of a dialogue, or a poem, uncertain.

For lovers of exploratory journeys, postmodern hopefulness that unapologetically dives into New Sincerity at home in George Saunders’s Lincoln in the Bardo, the dreaming lyrics of poets such as Li-Young Lee and Susan Mitchell, or nested narrative journeys made prevalent in Danielewski’s House of Leaves, Recidoro’s debut book communicates loss and depth through the messy lens of survival.