Little Worries: Print Series, by Sarah Ellis

I had never felt fear like this.

If this fear had a taste, it would be a blend of burnt coffee and bitter unripened citrus fruit with metallic notes. It would bite at the back of my tongue in a lingering, astringent sensation. If it had a smell, it would be the phantom scent of an electrical fire that cannot be located. If I could see the fear itself, it would be the shadow of an unknown man in my peripheral vision during that vulnerable moment preceding sleep.

Instead, I could only feel it nestling itself in the pit of my stomach and establishing roots.

• • •

I didn’t know it was an obsession at first. I found myself becoming more and more preoccupied with what could be wrong with my body after I noticed a strange feeling in my abdomen that lingered. Numerous doctor’s visits and blood tests confirmed only one thing: I was healthy. However, I began to research my “symptoms” more and more frequently as an attempt to soothe my anxiety. This swiftly developed into a compulsive behavior that consumed my evenings. I would lie awake and cry at night, afraid to sleep because I could feel in my bones that I wasn’t going to wake up in the morning. My relationships began to struggle as I became more and more fearful of being sick. I would fall to pieces if I discovered something new on my body or if I experienced what I perceived to be a new symptom. I needed constant reassurance that my fears were unfounded, but this was unobtainable. I became a stranger to my own mind as I lost control of my ability to rationalize.

I couldn’t trust what was real anymore. Every bodily sensation, every minor ache, and every flutter of discomfort sent shockwaves of panic through me. I spiraled into a world where even the most mundane symptoms became omens of catastrophic illness. Each Google search became a rabbit hole of dread, a confirmation that I was going to die soon. I was living with Hypochondriasis, or Health Anxiety Obsessive Compulsive Disorder.

As someone who has experienced varying degrees of mental health crises in my life, I knew it was time to seek professional help and medication during a specific panic attack. My (vaccinated, healthy) cat bit me and I became convinced that I had rabies instantly. As I was sobbing into my partner’s shoulder to the point of almost fainting, we both knew something had to change. Prozac soon acted as a powerful ally in working through my fears, removing some of the paralyzing anxiety and making room for me to start reestablishing reality. The hypochondria haze had been cleared, and I could see how severe it was in hindsight.

• • •

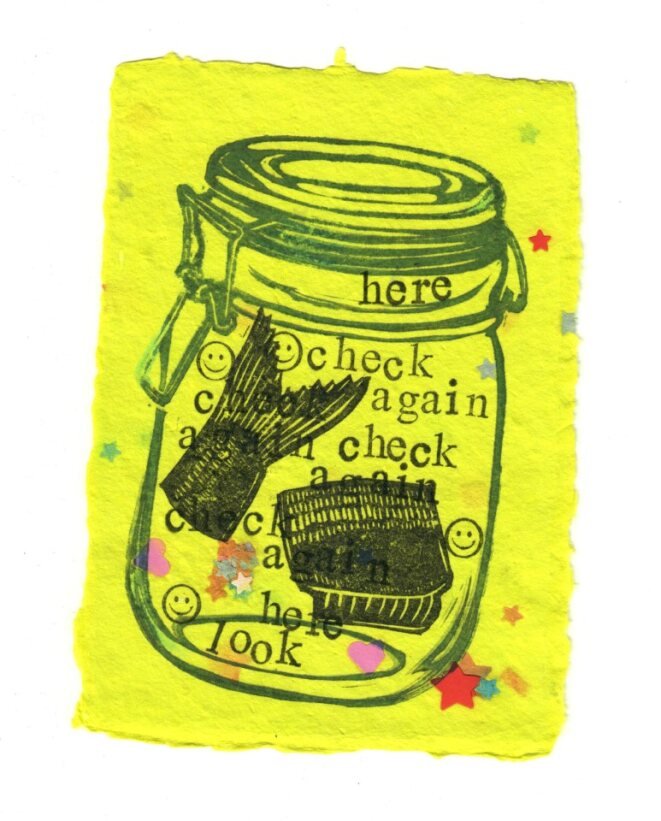

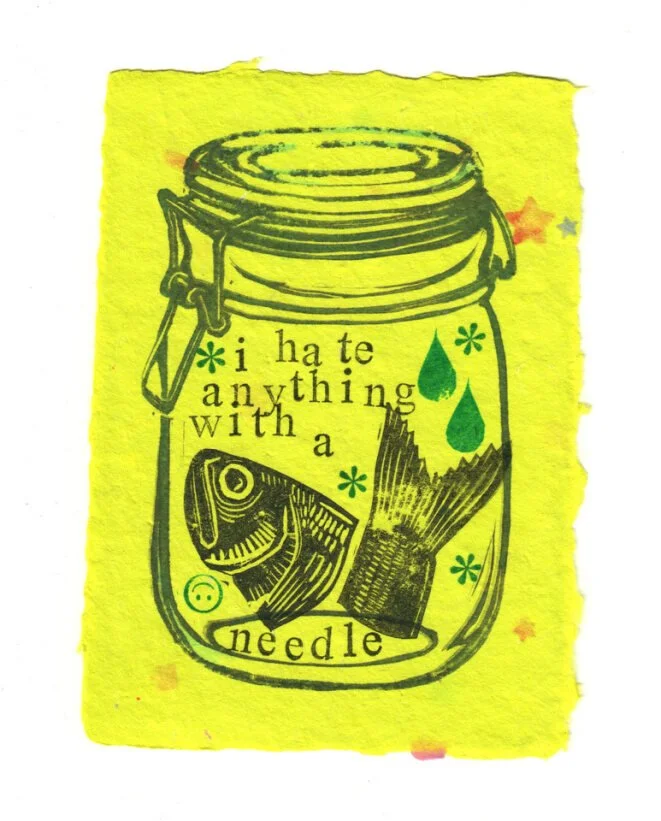

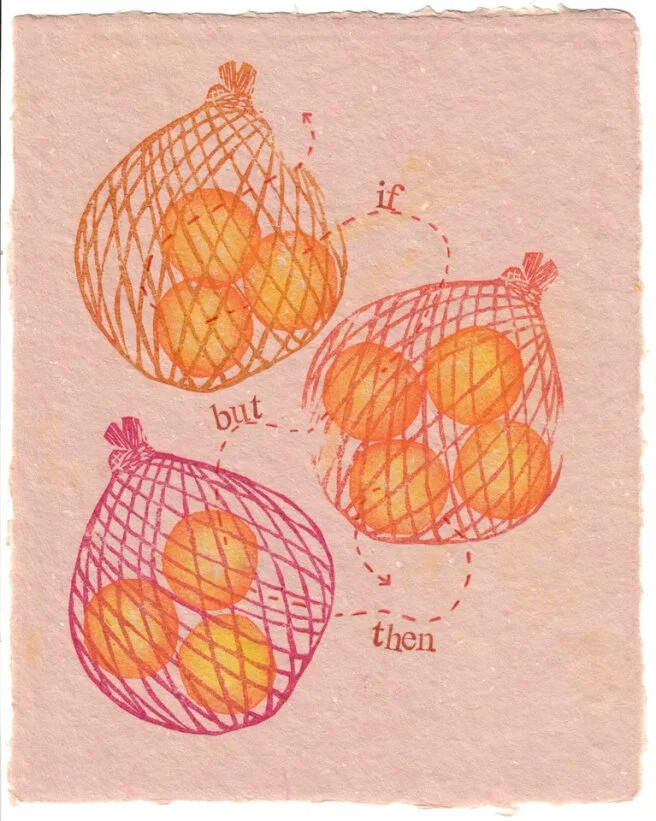

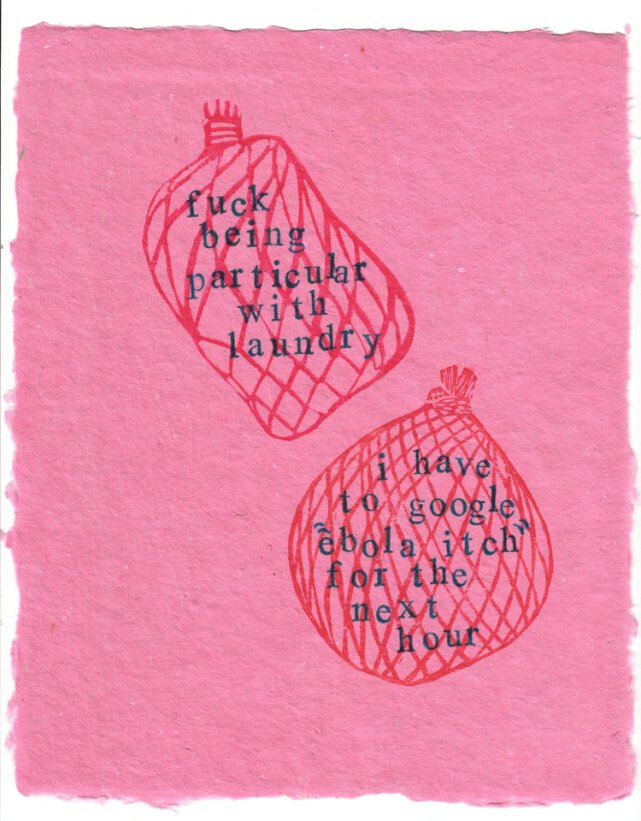

I would not describe my flavor of OCD as tidy, neat, or orderly. It was a messy, chaotic nightmare that eluded me for so long due to my own misconceptions of the disorder. I wanted to represent this in the suite of prints I created as Artist in Residence. The use of type in this work highlights the “little worries” that build pressure under the surface when processing rumination and compulsions. Seemingly inconsequential thoughts quickly turn into symptom-checking, a new bump on the body sparks excoriation, and a sore throat becomes a trip to urgent care.

The print pieces that I created as a part of this self-reflection use food products as a symbol of self-control being challenged. Canning food involves gathering ingredients at the peak of freshness and sealing them away to be ready for another time. Shelf stable, they are reassuring that nutrition (life) is still there. Things can happen to make these normally safe foods toxic and deadly, though. Botulism lingers as a threat in broken seals, cracked glass, and miscalculated temperatures. Humans can only control so much when there is an entire world of flora and fauna that we can’t see with the naked eye.

Relief printmaking, similar to canning, preserves something for the future. The carved blocks can be used repeatedly and in varying combinations, allowing them to be blended into new compositions. These blocks have an indefinite shelf life, and my collection now spans almost a decade of artistic exploration. Each piece was made specifically for this publication from newly carved blocks and will continue as an ongoing series.

Jacksonville, Alabama

2023.

NMR is a shared space among academics, artists, and activists to highlight and discuss their work. The artist in residence is chosen each year to share their work with the journal’s readership. Their work will be featured both in the print journal and website.

The 2023 artist in residence is Sarah Ellis.

Sarah is the Assistant Professor of Printmaking in the Department of Art and Design at Jacksonville State University. Her personal studio work consists of predominantly printmaking, paper arts, illustration, and sculpture. Sarah is a member of the LGBTQ+ community and participates in JSU’s Safe Zone program as a Facilitator. When she isn’t working, she enjoys self-care practices that include cooking, rock climbing, and spending time with her partner & her cat.