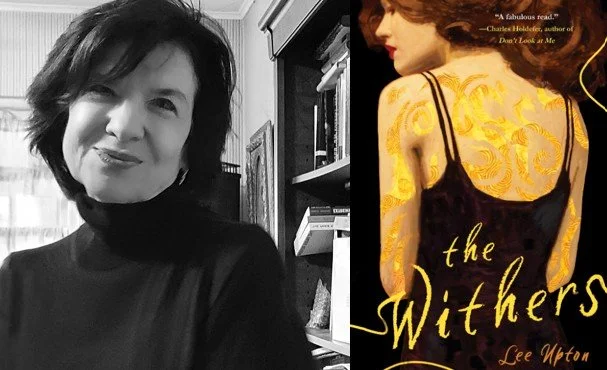

Lee Upton Discusses Her New Book, “The Withers”: Interview

In winter 2026, author Lee Upton answered questions about her new book “The Withers” with managing editor Wesley R. Bishop via email. Below is that conversation that explores Upton’s new novel, her writing process, and what the pandemic novel can still show us in a world after the onslaught of COVID.

Wesley R. Bishop: You have worked across poetry, fiction, and criticism. How do these different forms shape the way you think as a writer?

Lee Upton: It’s an adventure to work across genres. Each of the genres is like an aperture that allows us to gain access to what otherwise would be sealed. I began with poetry and continue with poetry, my great love, but I’m very fond of how omnivorous a novel can be. A novel can hold elements from multiple genres and that makes writing one profoundly exciting.

WRB: Looking back, what early experiences or influences most shaped your sense of what literature could do?

LU: My mother encouraged me at a very young age to take out any book I wanted from the adult section in the little library in Maple Rapids, Michigan. She also bought me Shakespeare’s plays, one after another, in paperback. That early start was enough to set me up for a lifetime of yearning.

WRB: Your work often centers interior life and moral pressure. When did those concerns first become important to you?

LU: Those concerns proved inescapable. I attended Mass each weekday morning throughout Catholic elementary school. My sense of guilt is well toned, let me tell you.

WRB: Do you think of yourself as working within particular literary traditions, or resisting them?

LU: I feel an affinity toward certain writers: Muriel Spark, Octavia E. Butler, Iris Murdoch, Banana Yoshimoto, Rachel Ingalls, Julio Cortázar, Kingsley Amis, Kazuo Ishiguro. I suppose I can’t help but lean toward an approach to realism that shades off into something otherworldly or spiritually unpredictable.

WRB: When you began The Withers, what kind of story did you think you were writing?

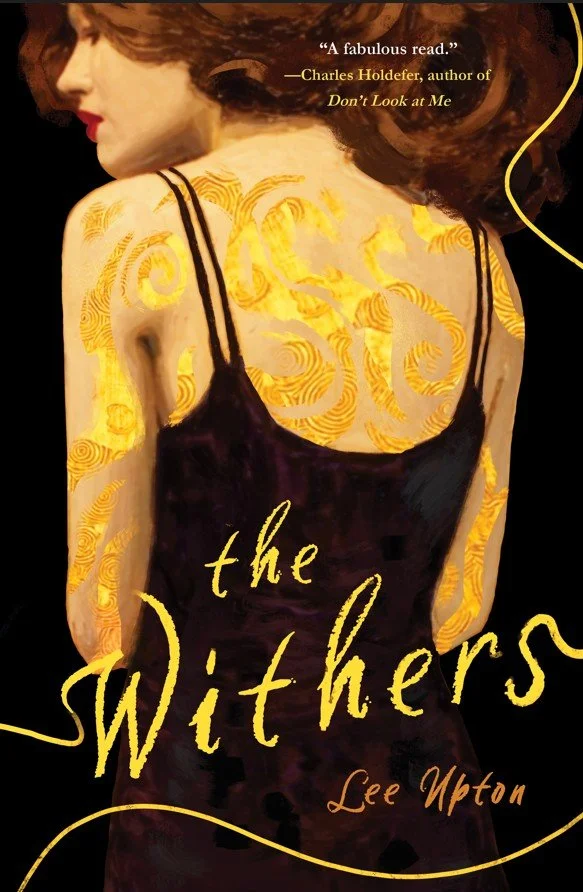

LU: I wasn’t sure at all. Years earlier I’d read a newspaper account about a couple who died overseas. When their bodies were returned home, all their internal organs were missing. That horrible report haunted me, and from thinking about the brutality of organ trafficking I began to create a story about a future world where traffickers roam nearly at will. At present, The World Health Organization estimates that as many as twenty percent of all organ transplants are derived illegally.

WRB: The novel imagines a near future shaped by medical authority and technological intervention. What questions or fears helped generate that world?

LU: It’s possible that we’re already inhabiting that world. Organ transplants, of course, save lives, and much new medical research is wonderfully promising. At the same time, it’s surely possible that untested or rarely tested medical interventions may lead to unimagined consequences.

WRB: The epidemic known as “The Collapse” remains vague. What did that openness allow you to explore?

LU: Yes, in my novel the origins of “the Collapse” cannot be strictly determined, just as theories about contested origins haunt accounts of the pandemic we endured and continue to endure. Organ failure in The Withers derives from consumption of food products, depending partly on the deterioration rate of certain components. Ironically, products marked “natural” and “organic” are most often the apparent source of the epidemic. In The Withers, as too often happens in actual life, large corporations’ powerful financial resources allow them to escape scrutiny.

WRB: I also would say survival in the novel is complicated and uneasy. How were you thinking about survival while writing the book?

LU: I brought to mind experiences of loss and grief and of physical pain as parts of our common inheritance.

WRB: How much of the novel was impacted by COVID? In what ways specifically or not?

LU: I finished the first complete draft of the novel before Covid. Oddly enough, I didn’t need to revise details about the epidemic in light of what we learned about Covid. As with the pandemic, in the novel origins are contested, controversial theories abound, even “warp speed” measures (although the novel doesn’t use that phrase) are part of the plot. Those elements appeared to be complications likely to arise in a region suffering from widespread organ failure. It may seem uncanny how much the novel tracks with the reality of Covid, but many cultural responses could be logically predicted. The desire to forget what happened to us during a horrible time—that desire is enacted by several characters and the larger culture in The Withers.

WRB: Some advance readers have noticed a fairy tale or mythic quality beneath the suspense. Were those influences conscious for you?

LU: Possibly many novels contain resonant subterranean stories—or hidden structures that are tied to fairy tales and myths. A fairy tale is directly referenced in The Withers: the story of Hansel and Gretel. In a way, the novel’s “unconscious” draws from that harrowing story.

WRB: The book moves quickly while maintaining careful attention to language. As a writer, how do you approach pacing at the sentence and scene level?

LU: I attempt to immerse myself in the main character’s perspective by discovering the particular rhythms in which she speaks and how her speech reveals her shifting emotional states in each scene. Riatta, the primary character in The Withers, has a distinctive way of speaking, partly because she is often ill and struggling to understand events that will become almost incomprehensible in their brutality.

WRB: In what ways does The Withers connect to, or depart from, your earlier work?

LU: The Withers taught me how to write my other novels. Tabitha, Get Up, my comic novel, was published in 2024, followed by Wrongful, a literary mystery, in 2025. The Withers will be out in June 2026, but my writing of it predates the other novels by several years. From The Withers I learned to sustain momentum, to orchestrate characters in a plot where actions have consequences, and to let a character’s flaws and strengths become meaningful over the arc of many pages.

WRB: The novel feels timely without pointing directly at specific events. How do you think about fiction’s relationship to the moment it is written in?

LU: We might want to escape our time, but inevitably our culture imprints itself on us even if we try to resist. When imagining future worlds we may be depicting the present in heightened form, making the present more visible.

WRB: Well said. What role do you believe writers can play during periods of social and ethical uncertainty?

LU: This is an individual matter, but I will say that during continual uncertainty we can allow ourselves to be humbled by questioning what we often assume, or are expected to assume, and by resisting whatever dehumanizes ourselves and others.

WRB: When writing about power, medicine, or technology, how do you avoid turning fiction into argument? Or, another way to ask this, should we avoid that?

LU: It can be helpful to let characters do the arguing in fiction—as a way to respect readers and to allow multiple voices and dramatic situations to reframe or extend our suppositions.

WRB: Do you think writers have particular responsibilities when imagining possible futures?

LU: The future outwits us, and yet I think we should allow ourselves to forecast possibilities. Maybe we can’t help it. The Withers is set in a near-future world where harrowing events take place, and yet I did feel the responsibility to imagine love and deep friendship and enduring loyalty and the triumph of courage over despair.

WRB: What do you hope readers feel or think as they move through The Withers?

LU: I suppose the plot moves between dread and hope. There’s also so much love some of the characters feel for one another. Plus, there’s a fabulous dog. Which is always hopeful: a good and faithful dog among good and faithful people.

WRB: What do you hope stays with them after they finish the book?

LU: I hope readers feel ever-renewed compassion for those who are outcasts or in any way marginalized. I hope, too, that The Withers provokes continued reflections not only in abstract terms but on a personal level about illness, grief, friendship, obsession, intuitive understanding, and the resources that genuine love offers us.

WRB: Finally, what keeps you committed to writing now?

LU: It’s a matter of tremendous luck to find an art that allows us to keep opening up more and more possibilities for discovery. Right now I’m working on a novel that is defeating me daily, but it’s a good struggle, and I have to believe that eventually the work will cohere. There’s so much rejection attached to writing, and so the act of writing itself needs to generate pleasure. The challenge is ongoing, but it’s thrilling when something we could never plan for emerges on the page or screen. It’s like an interior imp, if we keep working, will show its quirky little face and startle us. We get glimpses of something we’d never see otherwise. I’ll always be grateful that the act of writing can make such surprises happen.

Thanks so very much for these terrific questions!

WRB: Thank you for taking the time to answer them!